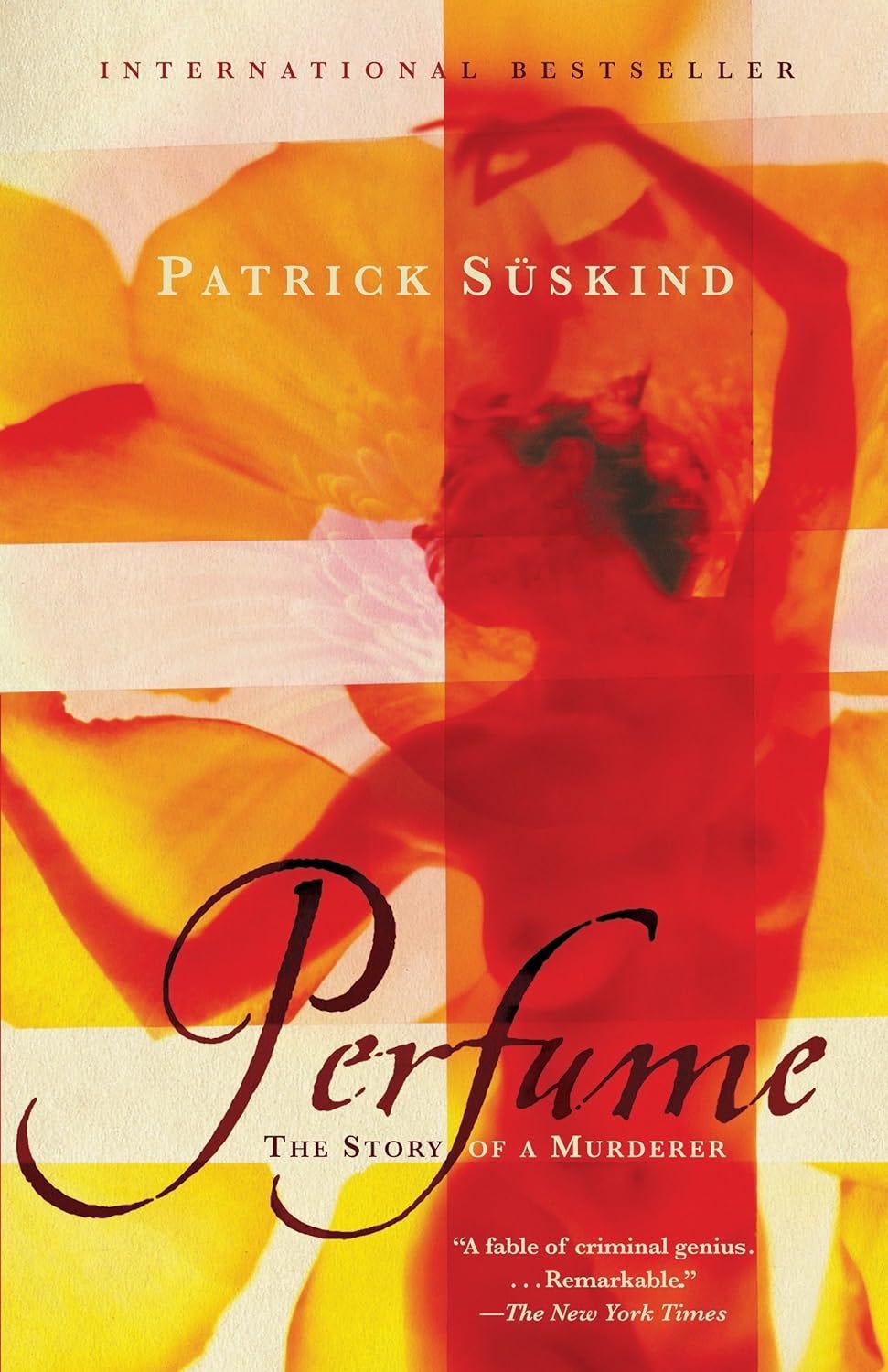

I'm about two-thirds of the way through a strange little book: Perfume (Patrick Suskind, 1985). The story is set in 18th-century France. It was recommended as an excellent study of how to evoke the sense of smell in writing.

As usual, I had no idea what I was getting into. I was soon reminded of another book: The Tin Drum (Gunter Grass, 1959). I did not enjoy The Tin Drum. In fact, back in the day when I/we felt it a personal failure to abandon a book once started, I gave The Tin Drum several hundred pages, then cast it aside.

Perfume, like The Tin Drum, is a dark, absurd tale with an unlikeable, no, repellant protagonist. After a few pages, I paused my reading to take a closer look and found that, like The Tin Drum, Perfume was translated from German. I know nothing of German literary history, but have to wonder if there was any conscious connection—probably some genre I am ignorant of. Thankfully, Perfume is a short book—only 255 pages, compared with The Tin Drum's 600. But both books were produced as films—Perfume in 2006, and The Tin Drum in 1979, winning the 1980 Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. So what do I know?

But that’s not why we are here.

We're here to have a look at how Patrick Suskind gets maximal effect, making words evoke the sensory detail of smell.

So far, I've found five categories of techniques:

1) I'll call this “description by naming the source”, or, shall we say—by nouns:

"In the period of which we speak, there reigned in the cities as stench barely conceivable to us modern men and women. The streets stank of manure, the courtyards of urine, the stairwells stank of moldering wood and rat droppings, the kitchens of spoiled cabbage and mutton fat; the unaired parlors stank of stale dust, the bedrooms of greasy sheets, damp featherbeds, and the pungently sweet aroma of chamber pots. The stench of sulfur rose from the chimneys, the stench of caustic lyes from the tanneries..." (p. 2-3)

That's half of the paragraph.

So here we have straightforward references to exactly WHAT it is that is causing the odor. It's not a description of the odor. The reader understands through reference to personal experience.

2) I'll call this one “description by simile”:

“…even the king himself stank, stank like a rank lion, and the queen like an old goat.” (p. 4)

3) By metaphor:

"Thousands upon thousands of odors formed an invisible gruel that filled the street ravines…" (p. 33)

4) By adjective:

"It was fresh, but not frenetic. It was floral, without being unctuous. It possessed depth, a splendid, abiding, voluptuous, rich brown depth—and yet was not in the least excessive or bombastic." (p. 60)

5) By effect:

"The scent was so heavenly fine that tears welled into Baldini's eyes... Baldini closed his eyes and watched as the most sublime memories were awakened within him. He saw himself as a young man walking through the evening gardens of Naples; he saw himself laying in the arms of a woman with dark curly hair and saw the silhouette of a bouquet of roses on the windowsill as the night wind passed by...” (p. 85)

What I find surprising is that Suskind’s most common technique, by far, is the first. I would have thought simile and metaphor would dominate in such an obviously “literary” novel. Here we are, trying to work up some clever metaphor, while Suskind lets the reader’s direct knowledge do the job. He names things and our brains take over.

Of the five, I find the last the most intriguing, least exploited, and hardest to pull off. If I smell boxwoods, I am transported to the entry of my grandmother’s house. It is a jolt, a nearly physical displacement back to that exact location. No other scent has as strong an effect on me. I’d love to develop the writing skill to use scent as a memory trigger for characters.

Coincidentally, just today, after writing this newsletter, including the boxwood reference, I was sorting old family slides for scanning. Lo-and-behold, there’s an image of Grandmary in her yellow Easter dress, hat, and gloves, in front of her stoop, flanked by those boxwoods—circa 1968. Priceless.

When I finish reading Perfume, I’ll let you know my response to the story itself. There’s really only one big plot question, and it seems impossible that Suskind can bring this all back around to the answer, but we trust that he will, and that suspense alone keeps us in this nightmare.

In the meantime, do you know of any other writers who excel in the smell category?

Funny, we romanticize castle life, but just yesterday I read an account of what castle life was really like.

And then this .... Very instructive of how to evoke the olfactory senses through words in a powerful way.

Can't imagine having to live with the blend of all those smells together, though.

No thanks.

I first bumped into "Perfume" when I was searching for a movie poster for a high school graphic design project. Now, 8 years later, I'm bumping into the book version on a Substack post that I found after the author commented on one of my Notes. Life certainly likes to keep us on our toes.

Anyways, this was a really insightful post! I think the description technique that I tend to forget most frequently is "by effect". Recently, I watched this video by one of my favorite Youtubers (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qMSYAxJeCu4&t=1760s) on writing description. In it, he'd also analyzed several famous books and noted that one of the most compelling ways to describe setting is to capture its emotional effect on the characters. I'll certainly be thinking about this technique a lot throughout this week.